Israeli project to substitute poisons with owls to control rodents is a stunning success with regional implications, held up only by politics. Such as the Gaza war

Ruth Schuster. Apr 8, 2024

Apr 8, 2024What inadvertent garnish would you prefer on your food: traces of rodenticide or bird droppings?

Leaving aside the properties of raptor doo, the fact is that chemicals used to kill rodents are also toxic to humans and the wild animals that eat the poisoned rodents. Hence the Barn Owl Initiative – born in Israel and spreading – to encourage the birds’ proliferation in agricultural areas for rodent control.

How does one encourage barn owls? By placing nesting boxes on stilts in the fields, high above ground, in order to thwart ground-based predators such as foxes.

The owls love them, according to project leader Yossi Leshem, zoology professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University and former head of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel.

The project’s pilot in 1983, in Kibbuutz Sde Eliahu, involved 14 nesting boxes. They were a hit with the owls. By 2008 the project had reached 730 boxes and the initiative was declared a national project.

Today there are about 5,000 owl-nesting boxes in central and northern Israel – though, Leshem qualifies, some were damaged in the current flare-up with Hezbollah. There are also 1,200 in Cyprus, 400 in Jordan, 400 in Switzerland, about 100 in the West Bank and 50 in Morocco. Open gallery view

Various kibbutzim and moshavim in the Negev wanted barn owl boxes too, but to support nesting owls one needs a dependable rodent population – and try relying on micromammals in the desert.

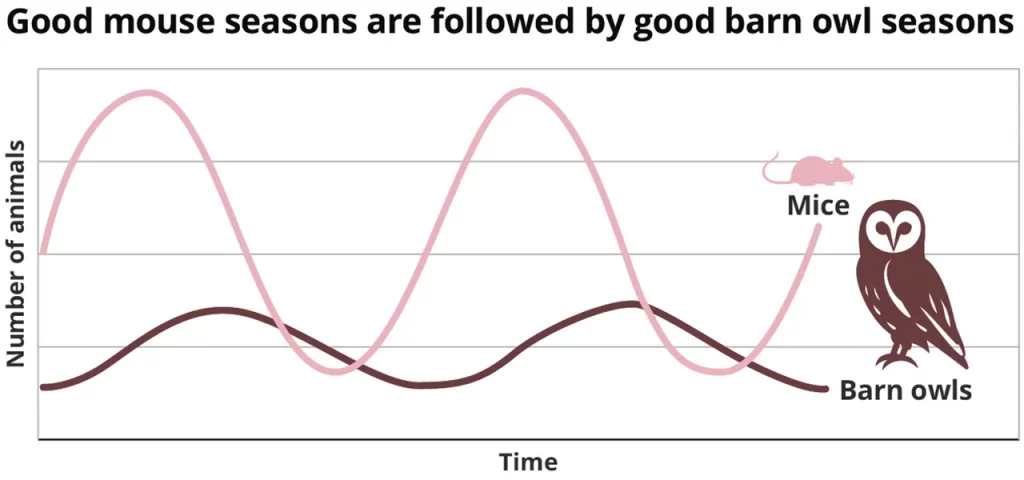

“The mouse population is sinusoidal. When there’s lots of water and vegetation, you get lots of mice,” Leshem explains. When there isn’t a lot of rain, you don’t get a lot of mice. All Israel is considered semi-arid, but the Negev desert is particularly sub-ideal.

In Jordan, the project was advocated by its former head of Military Intelligence Mansour Abu Rashid, who Leshem met pursuant to owl-tracking research by Dr. Yoav Motro at Israel’s Agriculture Ministry showing that owls do not respect international boundaries. Subsequent joint seminars with Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian farmers proved persuasive, Leshem says. (That said, at present the Palestinian branch of the project is on hold because of the Gaza war.)

Switzerland became involved through Prof. Alexandre Roulin of Lausanne University. “In 2012,” Leshem says, “we persuaded the Swiss president to tour Roulin’s nesting boxes in Switzerland with 150 ambassadors, including 12 from Arab nations.” Among them was one from the Vatican. Open gallery view

Papal blessings

The initiative is a win-win-win. Owls eat. Mice get quickly swallowed whole rather than suffer a slow, agonizing death by poison. We eat chemically cleaner food. The wild animals who eat rodents are spared. The farmer economizes on chemicals and gets rodenticide services for free, providing only maintenance for the boxes. This project is so virtuous that even the pope is on board.

Cyprus joined in 2015 through Birdlife Cyprus; some of its nesting boxes are in the buffer zone with Turkey. “We went to observe them just two weeks ago – there are eggs in the boxes,” Leshem says happily.

Upon Israel reaching a treaty with Morocco in 2020, collaboration ensued there too. Israeli tourism to Morocco is on ice at present but the project forges on, the professor adds. There was thinking that Dubai would join too.

Why? They grow dates in the United Arab Emirates, Leshem says. Anyway, an Emirati arm of barn owls without borders has yet to arise, but seven nations have joined so far.

And on May 11, 2019, Leshem and representatives from the Middle Eastern portion of the project met with Pope Francis at the Vatican for 45 minutes. It was a Shabbat during Ramadan, Leshem recalls, and being observant he was residing within walking distance. Open gallery view

“The pope was very enthusiastic about cooperation via owls,” Leshem says, adding, “we gave him a picture of an owl.”

Leshem also presented the pope with a bronze statue of a swift. “There are about 80 pairs of swifts nesting on the Western Wall,” he explained. More also nest on the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, he adds. In 2017 the British sculptor Mark Coreth created a sculpture, the “Tree of Hope,” with swifts. Why swifts? Because they don’t know boundaries, and happily nest on buildings of all faiths. Hearing about the meeting with the pope, Coreth made a swift for him. And Leshem and the pope agreed to pray that evening, each according to their faiths, the professor recalls. Open gallery view

Why choose the barn owl out of all predatory birds? Because it gets 95 percent of its nutrition from rodents and is associated with humans. Barn owls are known thusly because they nest in our barns, Leshem explains.

Where did they nest before the Neolithic invention of farming and silos? In trees and rock crevices, he answers. Also, these aviating pesticides hunt in open fields, not in forests.

Not that Israel has much forest to inconvenience the owls. But conveniently for us, our fields of wheat and chickpeas are the barn owl’s ideal, not orchards and conglomerations of planted trees (though voles and hares molesting apple trees have been a problem in Central Europe, it appears; barn owl rodent control may not help much with that).

In any case, the concept is to reduce agricultural use of rodenticides, which doom the micromammals to a hideous death – and do us no favors either. If ever there was a project suitable for regional cultivation, this is it.

The dove of peace may be ailing, but the barn owl of brotherly borderlessness could yet take off and usher in a new era of cooperation.

An uncertain bird

Tapping the natural world is a U-turn for humanity. We began our war against inconvenient housemates using natural means, but turned to poisons thousands of years ago. Ancient Egyptians plagued with lice used combs and shaved, but also resorted to applying date mush to their skin and bicarbonate of soda to the homes. The ancient Chinese tried to effect the miracle of licelessness with mercury. Well, if you kill the host…

As for micromammals, when humans began farming in the NeolithicRevolution around 10,000 years ago, the rodents hailed the opening of the world’s first supermarket. Cats subsequently and consequently joined our habitats, certainly in Egypt – which, by the way, also has what may be the world’s first rat trap: a ceramic device with a trapdoor mechanism found in 1891 at Kahun.

Feline exploitation was probably more noticeable than the commensal relationship that emerged with owls, who had also noticed the bounty. While the cat moved onto our laps, the silent predators of the sky nested in our barns.

Silent in flight, maybe. In Hebrew, barn owl is “teen-sheh-met,” an onomatopoeia imitating the asthmatic sound of their whoo-whoo cries, according to one source. Frankly, the barn owls of YouTube sound more like machinery seizing up.

Note that there are 15 barn owl species around the world but Israel has just one “tinshemet“: Tyto alba, says Prof. Yoav Perlman, director of SPNI’s Birdlife Israel. They’re not endangered, though they are vulnerable to ecological processes such as agricultural intensification, which is manifested in shifts to crops that are less favorable for barn owls and intensifying pesticide use, he points out.

Actually, according to linguistics expert Elon Gilad, we don’t know to which bird the biblical “tinshemet” refers. “The earliest translation [of the Hebrew Bible], the Septuagint, has it as some kind of purple bird,” he says.

Tinshemet appears in Leviticus among the birds we are to regard as “detestable” and not eat. That list is long, but we no longer know what some of them are. “Nesher” is vulture in modern Hebrew, but some translations say “eagle.” Tinshemet is referred to as horned owl, little owl, or just owl.

Among the first to identify tinshemet as owl was the medieval rabbi David Kimhi (“the Radak,” 1160-1235). Even so: “The word was actually used for a variety of different species of birds in the 19th century, including flamingos, storks and bats, but eventually following Mendele Mocher Sforim, we use it for an owl,” Gilad sums up.

Anyway, the barn owl project began with 14 nesting boxes and gained the status of national project in 2008. Today it is funded by the Agriculture Ministry and Regional Cooperation Ministry, though not the Environmental Protection Ministry (which provided funding from 2005 to 2010, and then stopped). However, it points out it gave this “important project” seed money (420,000 shekels) – but actually pest control in agriculture is the Agriculture Ministry’s fief.

A good mouse year

How much “damage” do rodents actually do? There are more than 2,200 rodent species, and they all like grain and fruit. If we believe in God, then he made them and they are perfect. Even if we don’t believe, they still fulfill a host of ecological functions. But they need to eat.

There aren’t even ballpark real estimates for rodent damage in Israel or anywhere else – just “a lot.” It fluctuates, and they cause damage not only by eating but by relieving themselves in our stocks, and/or introducing fungi and bacteria that spoil the grain. One can’t even feed rat-spoiled crops to livestock, it has been pointed out. Also, some insects such as beetles and mites, which we don’t like either, dote on rodenticide. Just when you thought it was safe to swim in the grain silo…

In short, rodent damage varies by region, season and time, from insignificant to a third of the crop, to near-total crop loss in a good mouse year. In Israel, when the Hula northern wetlands were drained for agriculture, one upshot was a massive increase in rodents, leading farmers to spray vast amounts of pesticides. But they kill more than the pests.

About half a billion birds fly over Israel each year, migrating between Africa and Eurasia. “To kill a rodent it takes 5 grains of rat poison, but the farmers dispersed large amounts. The poison also gets concentrated in the rodent,” Leshem says. “The hawk sees a weakened mouse outside, staggering about and they eat them easily and the poison concentrates in them too. In turn, then they die.” Poison is also applied to crops fed to livestock that we exploit. We sow, and we reap.Open gallery view

Hello stranger

Poison works. How effective is rodenticide by owl?

In a good mouse year, i.e., when the food is abundant, a pair may lay five to 13 eggs each year, Leshem says. An owl couple with chicks will eat between 2,000 to 6,000 rodents a year, depending on how many owlets they have.

“The owls can’t exterminate the rodents, but they can significantly reduce the population,” he elaborates, adding that in bad mouse years, owls will lay fewer eggs or even none.

They’re not migratory, Perlman confirms. But if the mouse supply just isn’t enough, they may fly many kilometers to hunt, and they don’t care about borders.

Is the project working? Sure – use of pesticides to control rodents has decreased by more than 50 percent since the initiative went national in 2008, Leshem says. In a good mouse year, when the owls are stuffed to the gills and happy and proliferating madly, farmers can settle for only applying spray to rodent burrows.

As the owl wings through the night skies of the Middle East (and Switzerland), seeking the rodents that crave our grain with its binocular vision and extraordinary ears, it is able to hear a hamster from a vole from a mouse taking a stroll from 30 meters (nearly 100 feet) away. Its beautiful heart-shaped face speaks to us of love love love, but to them it’s a satellite dish that focuses the noise of rustling rodents that they proceed to swallow whole. “After nine hours it vomits the pellet – bones, feathers, and teeth and claws,” Leshem says helpfully. “We can see these pellets by the nesting boxes and see what they ate.” Yes, the project is working.

Its only real natural enemy is the giant eagle owl, and us, in the form of habitat destruction and the poisons we spray. And why yes, sometimes other birds squat in those nesting boxes, such as the invasive mynah. At least if it does, it can imitate that unsettling screech of the barn owl, silent predator of the night.